A gentle introduction to support vector machines using R

Introduction

Most machine learning algorithms involve minimising an error measure of some kind (this measure is often called an objective function or loss function). For example, the error measure in linear regression problems is the famous mean squared error – i.e. the averaged sum of the squared differences between the predicted and actual values. Like the mean squared error, most objective functions depend on all points in the training dataset. In this post, I describe the support vector machine (SVM) approach which focuses instead on finding the optimal separation boundary between datapoints that have different classifications. I’ll elaborate on what this means in the next section.

Here’s the plan in brief. I’ll begin with the rationale behind SVMs using a simple case of a binary (two class) dataset with a simple separation boundary (I’ll clarify what “simple” means in a minute). Following that, I’ll describe how this can be generalised to datasets with more complex boundaries. Finally, I’ll work through a couple of examples in R, illustrating the principles behind SVMs. In line with the general philosophy of my “Gentle Introduction to Data Science Using R” series, the focus is on developing an intuitive understanding of the algorithm along with a practical demonstration of its use through a toy example.

The rationale

The basic idea behind SVMs is best illustrated by considering a simple case: a set of data points that belong to one of two classes, red and blue, as illustrated in figure 1 below. To make things simpler still, I have assumed that the boundary separating the two classes is a straight line, represented by the solid green line in the diagram. In the technical literature, such datasets are called linearly separable.

In the linearly separable case, there is usually a fair amount of freedom in the way a separating line can be drawn. Figure 2 illustrates this point: the two broken green lines are also valid separation boundaries. Indeed, because there is a non-zero distance between the two closest points between categories, there are an infinite number of possible separation lines. This, quite naturally, raises the question as to whether it is possible to choose a separation boundary that is optimal.

The short answer is, yes there is. One way to do this is to select a boundary line that maximises the margin, i.e. the distance between the separation boundary and the points that are closest to it. Such an optimal boundary is illustrated by the black brace in Figure 3. The really cool thing about this criterion is that the location of the separation boundary depends only on the points that are closest to it. This means, unlike other classification methods, the classifier does not depend on any other points in dataset. The directed lines between the boundary and the closest points on either side are called support vectors (these are the solid black lines in figure 3). A direct implication of this is that the fewer the support vectors, the better the generalizability of the boundary.

Although the above sounds great, it is of limited practical value because real data sets are seldom (if ever) linearly separable.

So, what can we do when dealing with real (i.e. non linearly separable) data sets?

A simple approach to tackle small deviations from linear separability is to allow a small number of points (those that are close to the boundary) to be misclassified. The number of possible misclassifications is governed by a free parameter C, which is called the cost. The cost is essentially the penalty associated with making an error: the higher the value of C, the less likely it is that the algorithm will misclassify a point.

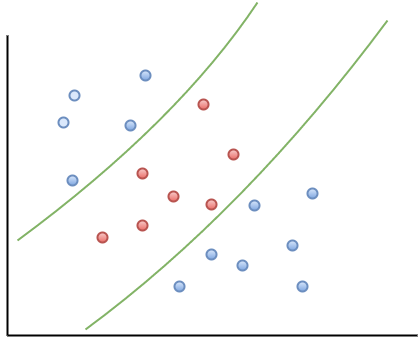

This approach – which is called soft margin classification – is illustrated in Figure 4. Note the points on the wrong side of the separation boundary. We will demonstrate soft margin SVMs in the next section. (Note: At the risk of belabouring the obvious, the purely linearly separable case discussed in the previous para is simply is a special case of the soft margin classifier.)

Real life situations are much more complex and cannot be dealt with using soft margin classifiers. For example, as shown in Figure 5, one could have widely separated clusters of points that belong to the same classes. Such situations, which require the use of multiple (and nonlinear) boundaries, can sometimes be dealt with using a clever approach called the kernel trick.

The kernel trick

Recall that in the linearly separable (or soft margin) case, the SVM algorithm works by finding a separation boundary that maximises the margin, which is the distance between the boundary and the points closest to it. The distance here is the usual straight line distance between the boundary and the closest point(s). This is called the Euclidean distance in honour of the great geometer of antiquity. The point to note is that this process results in a separation boundary that is a straight line, which as Figure 5 illustrates, does not always work. In fact in most cases it won’t.

So what can we do? To answer this question, we have to take a bit of a detour…

What if we were able to generalize the notion of distance in a way that generates nonlinear separation boundaries? It turns out that this is possible. To see how, one has to first understand how the notion of distance can be generalized.

The key properties that any measure of distance must satisfy are:

- Non-negativity – a distance cannot be negative, a point that needs no further explanation I reckon 🙂

- Symmetry – that is, the distance between point A and point B is the same as the distance between point B and point A.

- Identity– the distance between a point and itself is zero.

- Triangle inequality – that is the sum of distances between point A and B and points B and C must be less than or equal to the distance between A and C (equality holds only if all three points lie along the same line).

Any mathematical object that displays the above properties is akin to a distance. Such generalized distances are called metrics and the mathematical space in which they live is called a metric space. Metrics are defined using special mathematical functions designed to satisfy the above conditions. These functions are known as kernels.

The essence of the kernel trick lies in mapping the classification problem to a metric space in which the problem is rendered separable via a separation boundary that is simple in the new space, but complex – as it has to be – in the original one. Generally, the transformed space has a higher dimensionality, with each of the dimensions being (possibly complex) combinations of the original problem variables. However, this is not necessarily a problem because in practice one doesn’t actually mess around with transformations, one just tries different kernels (the transformation being implicit in the kernel) and sees which one does the job. The check is simple: we simply test the predictions resulting from using different kernels against a held out subset of the data (as one would for any machine learning algorithm).

It turns out that a particular function – called the radial basis function kernel (RBF kernel) – is very effective in many cases. The RBF kernel is essentially a Gaussian (or Normal) function with the Euclidean distance between pairs of points as the variable (see equation 1 below). The basic rationale behind the RBF kernel is that it creates separation boundaries that it tends to classify points close together (in the Euclidean sense) in the original space in the same way. This is reflected in the fact that the kernel decays (i.e. drops off to zero) as the Euclidean distance between points increases.

The rate at which a kernel decays is governed by the parameter – the higher the value of

, the more rapid the decay. This serves to illustrate that the RBF kernel is extremely flexible….but the flexibility comes at a price – the danger of overfitting for large values of

. One should choose appropriate values of C and

so as to ensure that the resulting kernel represents the best possible balance between flexibility and accuracy. We’ll discuss how this is done in practice later in this article.

Finally, though it is probably obvious, it is worth mentioning that the separation boundaries for arbitrary kernels are also defined through support vectors as in Figure 3. To reiterate a point made earlier, this means that a solution that has fewer support vectors is likely to be more robust than one with many. Why? Because the data points defining support vectors are ones that are most sensitive to noise- therefore the fewer, the better.

There are many other types of kernels, each with their own pros and cons. However, I’ll leave these for adventurous readers to explore by themselves. Finally, for a much more detailed….and dare I say, better… explanation of the kernel trick, I highly recommend this article by Eric Kim.

Support vector machines in R

In this demo we’ll use the svm interface that is implemented in the e1071 R package. This interface provides R programmers access to the comprehensive libsvm library written by Chang and Lin. I’ll use two toy datasets: the famous iris dataset available with the base R package and the sonar dataset from the mlbench package. I won’t describe details of the datasets as they are discussed at length in the documentation that I have linked to. However, it is worth mentioning the reasons why I chose these datasets:

- As mentioned earlier, no real life dataset is linearly separable, but the iris dataset is almost so. Consequently, it is a good illustration of using linear SVMs. Although one almost never uses these in practice, I have illustrated their use primarily for pedagogical reasons.

- The sonar dataset is a good illustration of the benefits of using RBF kernels in cases where the dataset is hard to visualise (60 variables in this case!). In general, one would almost always use RBF (or other nonlinear) kernels in practice.

With that said, let’s get right to it. I assume you have R and RStudio installed. For instructions on how to do this, have a look at the first article in this series. The processing preliminaries – loading libraries, data and creating training and test datasets are much the same as in my previous articles so I won’t dwell on these here. For completeness, however, I’ll list all the code so you can run it directly in R or R studio (a complete listing of the code can be found here):

The output from the SVM model show that there are 24 support vectors. If desired, these can be examined using the SV variable in the model – i.e via svm_model$SV.

The test prediction accuracy indicates that the linear performs quite well on this dataset, confirming that it is indeed near linearly separable. To check performance by class, one can create a confusion matrix as described in my post on random forests. I’ll leave this as an exercise for you. Another point is that we have used a soft-margin classification scheme with a cost C=1. You can experiment with this by explicitly changing the value of C. Again, I’ll leave this for you an exercise.

Before proceeding to the RBF kernel, I should mention a point that an alert reader may have noticed. The predicted variable, Species, can take on 3 values (setosa, versicolor and virginica). However, our discussion above dealt with a binary (2 valued) classification problem. This brings up the question as to how the algorithm deals multiclass classification problems – i.e those involving datasets with more than two classes. The libsvm algorithm (which svm uses) does this using a one-against-one classification strategy. Here’s how it works:

- Divide the dataset (assumed to have N classes) into N(N-1)/2 datasets that have two classes each.

- Solve the binary classification problem for each of these subsets

- Use a simple voting mechanism to assign a class to each data point.

Basically, each data point is assigned the most frequent classification it receives from all the binary classification problems it figures in.

With that said for the unrealistic linear classifier, let’s move to the real world. In the code below, I build SVM models using three different kernels

- Linear kernel (this is for comparison with the following 2 kernels).

- RBF kernel with default values for the parameters

and

.

- RBF kernel with optimal values for

and

. The optimal values are obtained using the tune.svm function (also available in e1071), which essentially builds models for multiple combinations of parameter values and selects the best.

OK, lets go:

I’ll leave you to examine the contents of the model. The important point to note here is that the performance of the model with the test set is quite dismal compared to the previous case. This simply indicates that the linear kernel is not appropriate here. Let’s take a look at what happens if we use the RBF kernel with default values for the parameters:

That’s a pretty decent improvement from the linear kernel. Let’s see if we can do better by doing some parameter tuning. To do this we first invoke tune.svm and use the parameters it gives us in the call to svm:

Which is fairly decent improvement on the un-optimised case.

Wrapping up

This bring us to the end of this introductory exploration of SVMs in R. To recap, the distinguishing feature of SVMs in contrast to most other techniques is that they attempt to construct optimal separation boundaries between different categories.

SVMs are quite versatile and have been applied to a wide variety of domains ranging from chemistry to pattern recognition. They are best used in binary classification scenarios. This brings up a question as to where SVMs are to be preferred to other binary classification techniques such as logistic regression. The honest response is, “it depends” – but here are some points to keep in mind when choosing between the two. A general point to keep in mind is that SVM algorithms tend to be expensive both in terms of memory and computation, issues that can start to hurt as the size of the dataset increases.

Given all the above caveats and considerations, the best way to figure out whether an SVM approach will work for your problem may be to do what most machine learning practitioners do: try it out!

[…] and then move on to clustering, topic modelling, naive Bayes, decision trees, random forests and support vector machines. I’m slowly adding to the list as I find the time, so please do check back again from time to […]

LikeLike

A prelude to machine learning | Eight to Late

February 23, 2017 at 3:13 pm

I am getting this error while tuning the SVM on my data set. Few suggestions on google included removing date and factor columns. Could you suggest a better approach?

Error in if (any(co)) { : missing value where TRUE/FALSE needed

LikeLike

abhim7011

April 12, 2017 at 1:28 am

I just learned that we should scale our continuous variables and create dummy variables for the categorical ones. Correct me if I am wrong. Also please confirm if this will help avoid the error in the above comment.

LikeLike

abhim7011

April 12, 2017 at 5:34 am

Thanks for your question. Scaling is generally a good idea for data that has large variations. And, yes, you will need to code categorical variables.

Hope this helps.

Regards,

K.

LikeLike

K

April 12, 2017 at 3:10 pm

Re the error you mentioned in your first comment, check out this thread on stackoverflow.

Regards,

K.

LikeLike

K

April 12, 2017 at 3:12 pm

[…] a year ago, I wrote a piece on support vector machines as a part of my gentle introduction to data science R series. So it is perhaps appropriate to begin […]

LikeLike

An intuitive introduction to support vector machines using R – Part 1 | Eight to Late

June 6, 2018 at 9:56 pm