Archive for October 2023

The ethics and aesthetics of change

I recently attended a conference focused on Agile and systems-based approaches to tackling organizational problems. As one might expect at such a conference, many of the talks were about change – how to approach it, make a case for it, lead it etc. The thing that struck me most when listening to the speakers was how little the discourse on change has changed in the 25 odd years I have been in the business.

This is not the fault of the speakers. They were passionate, articulate and speaking from their own experiences at the coalface of change. Yet there was something missing.

What is lacking is a broad paradigm within which people can make sense of what is going on in their organisations and craft appropriate interventions by and for themselves, instead of imposing “change models” advocated by academics or consultants who have no skin in the game.

–x–

Much of the discourse on organizational change focuses on processes: do this in order to achieve that. To be sure, these approaches also mention the importance of the more intangible personal attitudes such as the awareness and desire for change. However, these too are considered achievable by deliberate actions of those who are “driving” change: do this to create awareness, do that to make people want change and so on.

The approach is entirely instrumental, even when it pretends not to be: people are treated as cogs in a large organizational wheel, to be cajoled, coaxed or coerced to change. This does not work. The inconvenient fact is that you cannot get people to change by telling them to change. Instead, you must reframe the situation in a way that enables them to perceive it in a different light.

They might then choose to change of their own accord.

–x–

Some years ago, I was part of a team that was asked to improve data literacy across an organisation.

Now, what is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the term “data literacy“?

Chances are you think of it as a skill acquired through training. This is a natural reaction. We are conditioned to think of literacy as skill a acquired through programmed learning which, most often, happens in the context of a class or training program.

In the introduction to his classic Lectures on Physics, Richard Feynman (quoting Edward Gibbons) noted that, “the power of instruction is seldom of much efficacy except in those happy dispositions where it is almost superfluous.” This being so, wouldn’t it be better to use indirect approaches to learning? An example of such an approach is to “sneak” learning opportunities into day-to-day work rather than requiring people to “learn” in the artificial environment of a classroom. This would present employees multiple, even daily, opportunities to learn thus increasing their choices about how and when they learn.

We thought it worth a try.

–x–

It was clear to us that data literacy did not mean the same thing for a frontline employee as it did for a senior manager. Our first action, therefore, was to talk to the people across the organization who we knew worked with data in some way. We asked them questions on what data they used and how they used it. Most importantly we asked them to tell us about the one issue that “kept them up at night” and that they wished they had data about.

Unsurprisingly, the answers differed widely, depending on roles and positions in the organizational hierarchy. Managers wanted reports on performance, year on year trends etc. Frontline staff wanted feedback from customers and suggestions for improvement. There was a wide appreciation of what data could do for them, but an equally wide frustration that the data that was collected through surveys and systems tended to disappear into a data “black hole” never to be seen again or worse, presented in a way that was uninformative.

To tackle the issue, we took the first steps towards making data available to staff in ways that they could use. We did this by integrating customers, sales and demographic data along with survey data that collected feedback from customers and presenting it back to different user groups in ways that they could use immediately (what did customers think of the event? What worked? What didn’t?). We paid particular attention to addressing – if only partially – their responses to the “what keeps you up at night?” question.

A couple of years down the line, we could point to a clear uplift in data usage for decision making across the organization.

–x–

One of the phrases that keeps coming up in change management discussions is the need to “create an environment in which people can change.”

But what exactly does that mean?

How does a middle manager (with a fancy title that overstates the actual authority of the role) create an environment that facilitates change, within a larger system that is hostile to it? Indeed, the biggest obstacles to change are often senior managers who fear loss of control and therefore insist on tightly scripted change management approaches that limit the autonomy of frontline managers to improvise as needed.

Highly paid consultants and high-ranking executives are precisely the wrong people to be micro- scripting changes. If it is the frontline that needs to change, then that is where the story should be scripted.

People’s innate desire for a better working environment presents a fulcrum that is invariably overlooked. This is a shame because it is a point that can be leveraged to great advantage. To find the fulcrum, though, requires change agents to see what is happening on the ground instead of looking for things that confirm preconceived notions of management or fit prescriptions of methodologies.

Once one sees what is going on and acts upon it in a principled way, change comes for free.

–x–

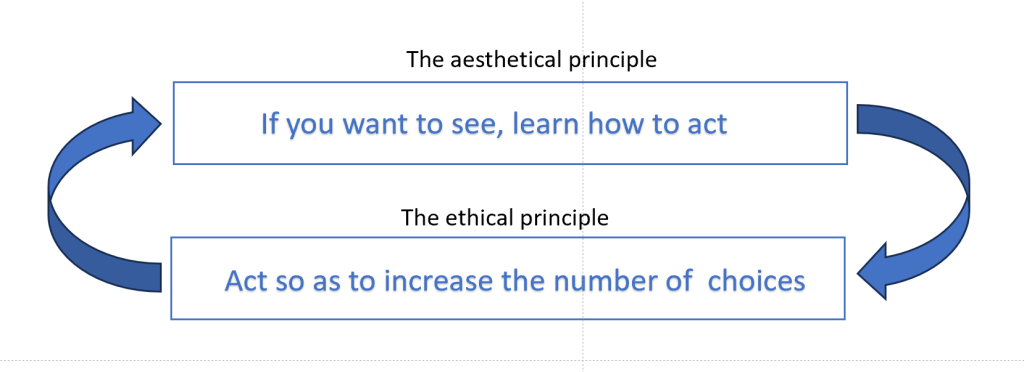

In his wonderful collection of essays on cognition, Heinz von Foerster, articulates two principles that ought to be the bedrock of all change efforts:

The Aesthetical Principle: If you want to see, learn how to act.

The Ethical Principle: Act always to increase choices.

The two are recursively connected as shown in Figure 1: to see, you must act appropriately; if you act appropriately, you will create new choices; the new choices (when enacted) will change the situation, and so you must see again…and so on. Recursively.

This paradigm puts a new spin on the tired old cliche about change being the only constant. Yes, change is unending, the world is Heraclitean, not Parmenidean. Yet, we have more power to shape it than we think, regardless of where we may be in the hierarchy. I first came across these principles over a decade ago and have used them as a guiding light in many of the change initiatives I have been involved in since.

Gregory Bateson once noted that, “what we lack is a theory of action in which the actor is part of the system.” Having used these principles for over a decade, I believe that an approach based on them could be a first step towards such a theory.

–x–

Von Foerster’s ethical and aesthetical imperatives are inspired by the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, who made the following statements in his best known book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus:

- It is clear that ethics cannot be articulated: meaning that ethical behaviour manifests itself through actions not words. Increasing choices for everyone affected by a change is an example of ethical action.

- Ethics and aesthetics are one: meaning that ethical actions have aesthetical outcomes– i.e., outcomes that are beautiful (in the sense of being harmonious with the wider system – an organization in this case)

By their very nature ethical and aesthetical principles do not prescribe specific actions. Instead, they exhort us to truly see what is happening and then devise actions – preferably non-intrusive and oblique – that might enable beneficial outcomes to occur. Doing this requires a sense of place and belonging, one that David Snowden captures beautifully in this essay.

–x–

Perhaps you remain unconvinced by my words. I can understand that. Unfortunately, I cannot offer scientific evidence of the efficacy of this approach; there is no proof and I do not think there will ever be. The approach works by altering conditions, not people, and conditions are hard to pin down. This being so, the effects of the changes are often wrongly attributed causes such as “inspiring leadership” or “highly motivated teams” etc. These are but labels that are used to dodge the question of what makes leadership inspiring or motivating.

A final word.

What is it that makes a work of art captivating? Critics may come up with various explanations, but ultimately its beauty is impossible to describe in words. For much the same reason, art teachers can teach techniques used by great artists, but they cannot teach their students how to create masterpieces.

You cannot paint a masterpiece by numbers but you can work towards creating one, a painting at a time.

The same is true of ethical and aesthetical approaches to change.

–x–x–

Note: The approach described here underpins Emergent Design, an evolutionary approach to sociotechnical change. See this piece for an introduction to Emergent Design and this book for details on how to apply it in the context of building modern data capabilities in organisations (use the code AFL03 for a 20% discount off the list price)