On the velocity of organisational change

Introduction

Management consultants and gurus emphasise the need for organisations to adapt to an ever-changing environment. Although this advice is generally sound, change initiatives continue to falter, stumble and even fail outright. There are many reasons for this. One is that the unintended consequences of change may overshadow its anticipated benefits, a point that gurus/consultants are careful to hide when selling their trademarked change formulas. Another is that a proposed change may be ill-conceived (though it must be admitted that this often becomes clear only after a change has been implemented). That said, many changes initiatives that are well thought through still end up failing. In this post I discuss one of the main reasons why this happens and what one can do to address it.

Change velocity

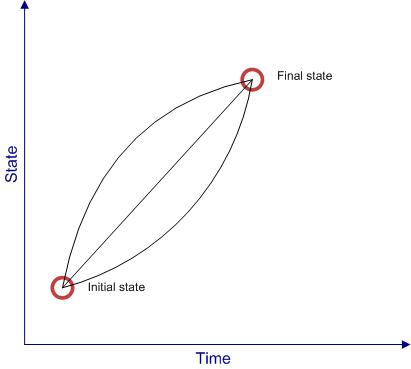

Let’s begin with a two dimensional grid as in Figure 1, with time on the horizontal axis and the state of the organisation along vertical axis (before going any further I should also mention that this model is grossly simplified – among other things it assumes that the state of the organisation can be defined by a single variable). We can represent the current state of a hypothetical organisation by the point marked as the “Initial state” in Figure 1.

Now imagine that the powers that be have decided that the organisation needs to change. Further, let’s imagine (…and this is hard) that they have good advisors who know what the organisation should look like after the change. This tells us the position of the final state along the vertical axis.

To plot the final state of the organisation on our grid we also need to fix its position along the horizontal (time) dimension- that is, we need to know by when the change will be implemented. The powers that be are so delighted by the consultants’ advice that they want the changes to be rolled out asap (sound familiar?). Plucking a deadline out of thin air, they decree it must be done by within a certain fixed (short!) period of time.

The end state of the organisation is thus represented by the point marked as the final state in Figure 1.

Let’s now consider some of the paths that by which the organisation can get from initial to the final state. Figure 2 shows some possible change paths – a concave curve (top), a straight line (middle) and a convex curve (bottom).

Insofar as this discussion is concerned, the important difference between these three curves is that each them describes a different “rate of change of change.” This is a rather clumsy and confusing term because the word change is used in two different senses. To simplify matters and avoid confusion, I will henceforth refer to it as the velocity of organisational change or simply, the velocity of change. The important point to note is that the velocity of change at any point along a change path is given by the steepness of the curve at that point.

Now for the paths shown in Figure 2:

- The concave path describes a situation in which the velocity of change is greatest at the start and then decreases as time goes on (i.e. the path is steepest at the start and then flattens out)

- The straight line path describes a situation in which the velocity of change is constant (i.e. the steepness is constant)

- The convex path describes a situation in which the velocity of change is smallest at the start and then increases with time. (i.e. the path starts out flat and then becomes steeper as the end state is approached)

To keep things simple I’ll assume that the change in our fictitious organisation happens at a constant velocity – i.e it can be described by the straight line. This is an oversimplification, of course, but not one that materially affects the conclusion.

What is clear is that by mandating the end date, the powers be have committed the organisation to a particular velocity of change. The key question is whether the required velocity is achievable and, more important, sustainable over the entire period in which the change is to be implemented.

An achievable and sustainable change velocity

Figuring out an achievable and sustainable velocity of change is no easy matter. It requires a deep understanding of how the organisation works at a detailed level. This knowledge is held by key people who work at the coalface of the organisation, and it is only by identifying and talking to them that management can get a good understanding of how long their proposed changes may take to implement and thus the actual path (i.e. curve) from the initial to the final state. Problem is, this is rarely done.

The foregoing discussion suggests a rather obvious way to address the issue –reduce the velocity of change or, to put it in simple terms, slow the pace of change. There are two benefits that come from doing this:

- First, the obvious one – a slower pace means that it is less likely that people will be overwhelmed by the work involved in making the change happen.

- The organisation can make changes incrementally, observe its effects and decide on next steps based on actual observations rather than wishful thinking.

- The organisation has enough time to absorb and digest the changes before the next instalment comes through. Implementing changes too fast will only result in organisational indigestion.

Problem is, the only way to do this is to allow a longer time for the change to be implemented (see Figure 3). The longer the time allotted, the lower the velocity of change (or steepness) and the more likely it is that the velocity will be achievable and sustainable.

Of course, there is nothing radical or new about this, It is intuitively obvious that the more time one allows for a change to be implemented, the more likely it is to be successful. Proponents of iterative and incremental change have been saying this for years – Barbara Czarniawska’s wonderful book, A Theory of Organizing, for example.

Summarising

Many well-intentioned organisational change initiatives fail because they are implemented in too short a time. When changes are implemented are too fast, there is no time to reflect on what’s happening and/or fix problems. The way to avoid this is clear: slow down. As in a real journey, this will give you time to appreciate the scenery and, more important, you’ll be better placed to deal with unforeseen events and hazards.

Kailash — an interesting metaphor to think about change in terms of acceleration curves, thanks.

But apart from not being able to measure “velocity”, every time you make a change, it might well have ripple effects, being a complex adaptive system. Or it might have no effect *up to a certain point*, with the system absorbing the change and continuing with business as usual — until you reach some threshold.

So since I know that you know this perfectly well, I’m a bit surprised to see you talking in the language of Newtonian physics 😉

Simon

LikeLike

Simon Buckingham Shum

January 17, 2013 at 9:38 pm

Hi Simon,

Thanks so much for reading and taking the time to comment. You’re absolutely right, of course, organisations are complex systems and the Newtonian view described in the post is not strictly applicable to such systems. Nevertheless, I have found this Newtonian analogy helpful when talking to executives about the importance of an appropriate pace of change – which, more often than not, means slowing down. Among other things, slowing down makes it easier to deal with the unforeseen consequences of change – the ripple effects- which are manifestations of complex/adaptive behaviour.

Regards,

Kailash.

LikeLike

K

January 17, 2013 at 10:34 pm

Kailash,

As I read this I also thought about the potential randomness of complex systems, but relaxed with it because at a meta level there are probably observable patterns.

But what about the S curve? Where is it as a likely pattern, and what does it say about adopting change slowly?

LikeLike

craigwbrown

January 18, 2013 at 10:54 am

Hi Craig,

Good point – the S curve is definitely more representative of a change process than any of the curves I have considered in the post. However, my intent was to make the point that, although the velocity will vary through the change process (as it does in the S curve), its overall magnitude (as reflected by the average, say) depends critically on the time allocated for the change to be implemented. The shorter the time, the larger the velocity, the less the time for reflection and the greater the chance that things that go wrong will remain undetected and uncorrected.

Regards,

Kailash.

LikeLike

K

January 18, 2013 at 4:46 pm